MES AYNAK, Afghanistan (AP) — Treasures from Afghanistan’s largely forgotten Buddhist past are buried beneath sandy hills surrounding the ancient Silk Road town of Mes Aynak — along with enough copper to make the land glow green in the morning light.

An estimated 5.5 million tons of copper, one of the biggest deposits in the world, could provide a major export for a war-ravaged country desperately in need of jobs and cash. But the hoped-for bonanza also could endanger rare artifacts that survived the rule of the Taliban and offer a window into Afghanistan’s rich pre-Islamic history.

“The copper mine and its extraction are very important. But more important is our national culture,” said Abdul Qadir Timor, director of archaeology at Afghanistan’s Culture Ministry. “Copper is a temporary source of income. Afghanistan might benefit for five or six years after mining begins, and then the resource comes to an end.”

The government is determined to develop Afghanistan’s estimated $3 trillion worth of minerals and petroleum, an untapped source of revenue that could transform the country. The withdrawal of U.S.-led combat forces at the end of 2014 and a parallel drop in foreign aid have left the government strapped for cash. It hopes to attract global firms to exploit oil, natural gas and minerals, ranging from gold and silver to the blue lapis lazuli for which the country has been known since ancient times.

Beijing’s state-run China Metallurgical Group struck a $3 billion deal in 2008 to develop a mining town at Mes Aynak with power generators, road and rail links, and smelting facilities. Workers built a residential compound, but were pulled out two years ago because of security concerns. Nazifullah Salarzai, a spokesman for President Ashraf Ghani, said the government is determined to finish that project.

Archaeologists are scrambling to uncover a trove of artifacts at the site dating back nearly 2,000 years which shed light on a Buddhist civilization that stretched across India and China, reaching all the way to Japan.

“The more we look, the more we find,” archaeologist Aziz Wafa said as he scanned hilltops pock-marked with bowl-shaped hollows where copper powder once was melted down and painted onto ceramics. Excavators have found silver platters, gold jewelry and a human skeleton as they have uncovered the contours of a long-lost town that once hosted elaborate homes, monasteries, workshops and smelters.

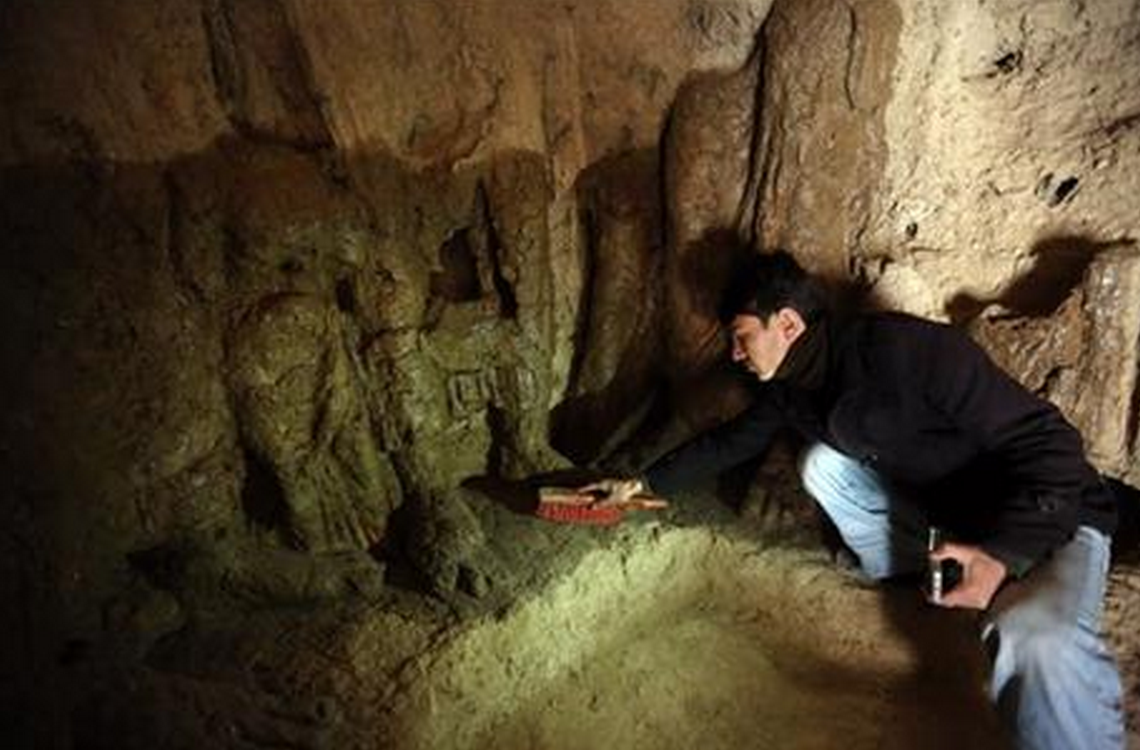

Behind Wafa is a cave in which three Buddhas are seated around a dome-shaped shrine known as a stupa. Two are headless; one was decapitated by looters who entered through a tunnel. The other head was removed by archaeologists and placed in storage along with thousands of other items.

Movable objects, including sculptures, coins and ceramics, are stored at the National Museum in Kabul. Larger objects, including stupas measuring eight meters (26 feet) across and statues of robed monks 7 meters (23 feet) tall remain at the sprawling site, which is closed off and protected by a special security force. The roads are lined with armed guards and the archaeologists have no telephone or Internet access.

Experts believe that proselytizing Buddhist monks from India settled here in the 2nd Century A.D. Like today’s miners, they were enticed by the copper, which they fashioned into jewelry and other products to trade on the Silk Road linking China to Europe.

The site was discovered in 1942 and first explored in 1963, but the excavations ground to a halt for two decades during the Soviet invasion, the civil war and the brutal rule of the Taliban in the late 1990s. Osama bin Laden ran a training camp at Mes Aynak in the years leading up to the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks and the subsequent U.S.-led invasion.

Until the giant Buddhas of Bamiyan were dynamited by the Taliban in 2001, few knew that Afghanistan was once a wealthy, powerful Buddhist empire. It still does not feature on the local education curriculum, which ignores the country’s pre-Islamic past. But at Mes Aynak the eroded remains of enormous feet testify to the colossal Buddhas that once towered over the valley.

Low world copper prices and a slowing Chinese economy have bought time for the archaeologists to uncover more artifacts, while the government seeks to find a way to unearth the copper without ruining relics.

The government has asked the U.N. cultural agency to survey mining sites and draw up plans to protect and preserve cultural heritage, said Masanori Nagaoka, UNESCO’s head of cultural affairs in Afghanistan.

The request is rooted in hope for better days, when tourists might replace the tense guards scanning the valley.

The archaeological value of the site “will outlast the life cycle of the Aynak mine,” an anti-corruption group called Integrity Watch Afghanistan said in a report. “The relics found could be a perpetual tourist attraction and would provide a new symbol of the historical foundation of the region and people.”