Afghanistan has a new mining law that aims to tap the potentially lucrative sector to fund the country’s post-war development but which critics say falls short of international standards and could encourage further conflict and corruption.

President Hamid Karzai signed the Law on Mines after it was finally passed, more than a year after being tabled, by the lower house of parliament on August 16, following the last-minute addition of guarantees that local communities will share in the proceeds of mining.

“The house approved the law with a new article, and based on it, 5 per cent of mining income will be spent on the people of the provinces where mines are located,” a member of parliament from northern Baghlan province, Obaidullah Ramin, told local media.

Passage of the law is expected to see a surge of contracts to mine copper and gold in various parts of the country, industry sources said.

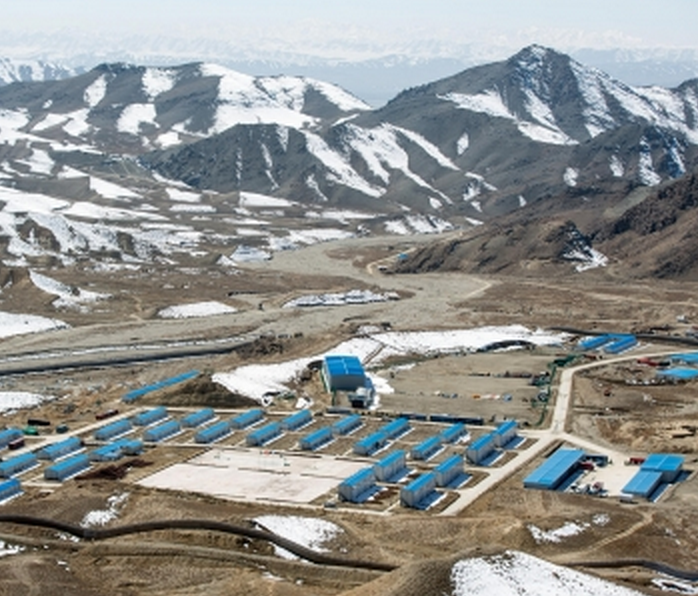

Two flagship deals, however, with China and India are unlikely to yield revenues any time soon, the sources said. The Indian state-led consortium Afisco (Afghanistan Iron & Steel Consortium) has been waiting for the new law to pass before finalising a US$10.8 billion deal to mine iron ore in Bamiyan; China has cooled on its US$3 billion copper deal at Mes Aynak, renegotiated large parts of the contract, and withdrawn its personnel after coming under regular Taliban attack.

Two flagship deals, however, with China and India are unlikely to yield revenues any time soon, the sources said. The Indian state-led consortium Afisco (Afghanistan Iron & Steel Consortium) has been waiting for the new law to pass before finalising a US$10.8 billion deal to mine iron ore in Bamiyan; China has cooled on its US$3 billion copper deal at Mes Aynak, renegotiated large parts of the contract, and withdrawn its personnel after coming under regular Taliban attack.

Critics say the new law does not deal with the fundamental issues of transparency, community monitoring of mining, social and environmental impact, and compensation for land use. It also lacks provision for fair and affordable dispute resolution.

Global Witness, a mining industry standards advocacy organisation in London, says these weaknesses do nothing to ensure that mining rights are not a source of conflict.

“Transparency over contracts and ownership, strong rules for open and fair bidding, and complaint mechanisms that local communities can actually use are increasingly routine elements of international best practice,” said Stephen Carter, of Global Witness’s Afghanistan team.

“These are the first things that should have been included in the law if the Afghan government and its international partners are serious about avoiding the very real threat of natural resources fuelling conflict and corruption, as they have in so many other countries.”

Afghanistan is said to sit on US$1 trillion worth of mineral assets, including gold, copper, iron ore, silver, a variety of minor metals and gems. It also has petrochemicals worth around US$2 trillion.

Resources revenues have been touted as the replacement for the billions that propped up the country for more than a decade.

Foreign combat troops are due to withdraw on December 31 and international aid organisations are reducing their exposure. The impact of this scaling down is already clear: economic growth of close to 14 per cent in 2012 fell, according to the World Bank and IMF, to 3.6 per cent last year.

For Javed Noorani, formerly of the independent think tank Integrity Watch Afghanistan and an expert on the resources sector, says there is no question that the omissions will fuel further corruption in a sector that has already slipped out of government control.

Noorani compared Afghanistan to Congo, a failed state cursed by its mineral wealth, which has been seized by warlords who fight over the proceeds in conflicts that have lasted decades and killed thousands.

Noorani compared Afghanistan to Congo, a failed state cursed by its mineral wealth, which has been seized by warlords who fight over the proceeds in conflicts that have lasted decades and killed thousands.

He believes he is witnessing the seeds of regional conflict, financed by Afghanistan’s minerals, in which his country reverts to the wasteland that attracted Osama bin Laden to use the Mes Aynak copper mine as a training base while he planned the September 11 attacks on the US.

Afghanistan’s transition, Noorani said, is not from war to peace, rather “from military conflict to resources conflict”. The battle for control of resources “may consign the country to a prolonged war”, he said. “The Taliban are not spectators to the sector but finance their war from revenues from the sector.”

After two votes – on April 5 and a run-off on July 14 – all 8.1 million votes are being audited under United Nations supervision after one candidate, Abdullah Abdullah, accused rival Ashraf Ghani of fraud.

The government has run out of money to pay civil service salaries, and the presidential hopefuls are squabbling over the terms of an agreement on how to resolve the impasse.

In the meantime, the minerals sector is being overrun by vested local interests, warlords, armed groups such as the Afghan Local Police, and resources including coal, chromite, gold and gems are being smuggled into bordering countries, further enriching criminal gangs.

“There is no shortage of countries around the world that have seen mining fund armed groups and fuel corruption. A strong law is the first step to making sure Afghanistan is not one of them,” Carter said. “Proper safeguards are not an obstacle to using Afghanistan’s resources to help the country – they are an essential precondition for it.”